Leo Strauss's infamous "esoteric" reading of John Locke

|

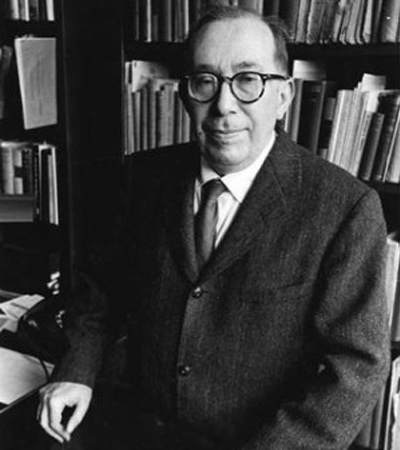

| Leo Strauss |

It is no secret that I am a fan of John Locke. I stole this blog’s name from the title of one of his books, after all. I am very impressed and inspired by his unique and refreshing combination of clear-headed reason and reliance on faith and scripture. I have to say I was a little dismayed and surprised when I saw that many or most political commentators today see John Locke as an atheist / deist / secularist, following the “Straussian” reading of Locke. This so strongly contradicted everything that I saw in my reading of Locke that it was quite baffling, and I felt a need to figure out what was going on.

The Reasonableness of Christianity was the first of John Locke’s works that I came across (see my thoughts here), as my interests (outside of my day job) are essentially Christian and religious. I found in Locke a scholar who taught that Christian revelation is not just reasonable, but that Christian religion is the best and only foundation for true reason. Locke wrote that Christianity is the most complete teaching of natural law - something no mere philosopher has ever come close to. These perspectives would not be much appreciated in academic circles today. I love reading Locke’s refreshing voice from the past as a reminder that politics and philosophy need not be purely secular, and that religious thinkers need not cede scholarship entirely to the godless. Also, I find in Locke’s words support for the claim that classical liberalism arose fundamentally from Christian assumptions and ideas, and therefore that the success and egalitarian ideals of the West are due to Christian origins.

From what I can tell, and as I noted recently, the Christian origins of classical liberalism and of the success of the West was commonly understood among non-Marxist intellectuals up until about 60-80 years ago but the idea has since been obscured, to the point where today any connection between liberalism on Christianity seems counterintuitive to most. Recent scholarship by Rodney Stark and Larry Siedentop has tried to revive the connection in the 21st century.

Reading Locke, any reader will notice theological assumptions and commentary throughout all of his writings, and the reader will see that Locke focuses significant energy on specifically religious projects like his A Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistles of St. Paul. In the face of this evidence, how does Leo Strauss get almost everyone to forget about or ignore the explicitly religious nature of Locke’s thinking? Let’s go through some examples of his “esoteric” readings of Locke. Lecture transcripts from a 1958 course by Strauss on Locke (from a collection at the University of Chicago) show his approach. In this course, the first of Locke’s works that Strauss approaches is Locke’s Essays on the Law of Nature, which opens with this theological argument for the existence of Natural Law:

Since God shows Himself to us as present everywhere and, as it were, forces Himself upon the eyes of men as much in the fixed course of nature now as by the frequent evidence of miracles in time past, I assume there will be no one to deny the existence of God, provided he recognizes either the necessity for some rational account of life, or that there is a thing that deserves to be called virtue or vice. This then being taken for granted, and it would be wrong to doubt it, namely, that some divine being presides over the world…it seems just therefore to inquire whether man alone has come into the world altogether exempt from any law applicable to himself, without a plan, rule, or any pattern of his life. No one will easily believe this, who has reflected upon Almighty God, or the unvarying consensus of the whole of mankind at every time and in every place, or even upon himself or his conscience.

The obvious meaning is that natural law arises from the existence of God and is consistent with reason. As in his other writings, Locke expresses a belief that reason and Christian religion are not just compatible but in fact part of the same whole. Strauss, who cannot bear the thought, takes this passage and focuses on that "provided" in the first sentence as a demonstration that Locke is hinting that he knows not everyone believes in God; and on that last clause as a demonstration that in reality for Locke natural law arises "independent of reflection on God," in Strauss’s words. In the end Strauss’s sophistry flips the paragraph, and all of Locke’s meaning, upside down to better match his (Strauss’s, not Locke’s) beliefs - namely, that natural law is independent of religion and that reason and religion are incompatible.

In another lecture, Strauss states that because Locke often references the Bible to support his claims, but doesn’t ALWAYS quote the Bible when he has opportunity to do so, we should take this a clue that Locke is not really relying on Christianity for his Natural Law. “In other words, it is not merely the quotations of the Bible but also the silence on biblical passages which could reasonably be expected in the context which have to be considered.” That method of textual analysis is a recipe for motivated reasoning. It is on these sorts of assumptions and the elevating of apparent inconsistencies in the text that Strauss reads into Locke the opposite of the plain meaning his words express.

In Strauss’s words, “Locke … creates the impression that this political natural law teaching stands and falls by the theological premise. The true premise, which is much closer to Hobbes, as we shall see, he never sets forth clearly.” The “true premise” as Strauss states later, according to his decoder ring, is that “Locke tried to present a natural law teaching which was not based on the acceptance of the existence of God.” But Locke needed to make it seem like his natural law theory was based on the existence of God because that “was necessary if he wanted to get any hearing.” This is plausible if you don’t dig too much into the specifics or context of the argument, and secularized academics ate it up.

But if Locke were an atheist or deist, why would he spend a significant portion of his life writing The Reasonableness of Christianity (in which he continues to argue exactly the opposite of Strauss’s contention) and poring over the Pauline epistles, generating 450+ pages of posthumously published notes? I was nervous when I started to read his A Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistles of St. Paul, that if Strauss was right I might find a subversive attempt to subtly undermine the reality of Christ and revelation. But no, Locke’s reading is a very straight reading through the Epistles, accepting Paul’s miraculous call and the divinity of Christ, and trying only to follow the wandering threads of Paul’s rhetoric in order to better understand what he is getting at. Faced with multiple interpretations of a complex author, Locke said of his approach that he “endeavoured to make St. Paul an interpreter to me of his own epistles.” I would also echo Locke on Locke, and suggest that, rather than rely on Strauss, we should endeavor to make Locke an interpreter to us of his own writings.

For me, everything points toward a straight reading of Locke as a devoutly religious man, and against Strauss’s self-serving esoteric reading. But what is Strauss’s game in all this? What is his objective in obscuring the Christian roots of Locke’s natural law theory and painting Locke as a secularist, “hedonist” and “sensualist,” despite all the evidence to the contrary? Strauss is difficult to pin down in terms of the usual political categories, and I’ve seen a variety of takes on Strauss from many different angles, so I sought to allow Strauss to be the interpreter to me of his own natural rights philosophy, by reading his Natural Right and History (online full text here).

First of all, I have to say that Strauss was brilliant - subversive but genius. Natural Right and History is filled with pithy remarks, strong and interesting conclusions, and a tremendous intellectual depth and breadth. It was fascinating reading, despite my fundamental disagreement with much of it. It was at times challenging to separate his commentary and summaries of other major intellectual figures from his own reasonings, but nonetheless a clear picture emerges.

Strauss wrote elsewhere of his favorable opinion of Heidegger’s natural law theory, and I think that much of Strauss, or at least the question at hand, can be made clear through this influence. As I understand it in a nutshell (not having read Heidegger myself, I don’t claim to fully understand the nuances, and maybe I’m going to butcher it), Heidegger was not a fan of The West. He thought that Western modernity forced mankind into an inauthentic existence, and that “Dasein” or “pure being” could only be found by rolling back Western metaphysics to a more natural existence in a pre-Socratic way of experiencing life. In Natural Right and History, Strauss expresses a similar sentiment, clearly influenced by Heidegger.

Strauss believed in a natural law not based on God, but (somewhat arbitrarily, in my opinion) on the idea of the classical philosopher as the natural and authentic way of being. The good consists of the natural inclinations and desires of man (like Rousseau and Heidegger but contra Christianity), specifically from a time of arts and philosophy uncorrupted. “Originally, philosophy had been the humanizing quest for the eternal order, and hence it had been a pure source of humane inspiration and aspiration. Since the seventeenth century, philosophy has become a weapon, and hence an instrument. It was this politicization of philosophy that was discerned as the root of our troubles.” Sounds like Strauss is not as much of a fan of Locke as I am.

Strauss cites Max Weber on “the prospects of Western civilization. He saw this alternative: either a spiritual renewal (‘wholly new prophets or a powerful renaissance of old thoughts and ideals’) or else ‘mechanized petrifaction, varnished by a kind of convulsive sense of self-importance,’ i.e., the extinction of every human possibility but that of ‘specialists without spirit or vision and voluptuaries without heart.’” Strauss accepts Weber’s premise of spiritual decay in the modern West (in the form of what sounds like an ossified Christianity), but rejects Weber’s extreme relativism in his inability to make a values-based decision between the three options he presents. Strauss rejects the idea of continuing in outdated religion, doesn’t address the proposal of “wholly new prophets,” and points us toward “a powerful rennaissance of old thoughts and ideals,” aka classical philosophy to replace Western Christian metaphysics.

Strauss makes a point of rejecting Weber’s extreme moral relativism, what Strauss calls “radical historicism.” Historicism is the idea that all truth and moral values are not objectively and universally true, but only apply to a given historical situation. Historicism is the principle behind the nihilistic postmodernism that militantly seeks to erase all objective truth and moral values. Strauss rejects this extreme postmodern position; however, his own philosophy is a nuanced version of postmodern relativism with only a sliver of difference. He says “we ought to welcome historicism as an ally in the fight against dogmatism,” by which he means the enemy is Christianity and other systems of belief that claim universal truths and values. The difference is that Strauss does accept the idea of natural law, which for him means a natural inclination in man to seek for something higher than pure sensualism and hedonism, though this inclination can be overridden by societal forces. Strauss declares that Greek classical philosophy gives us the highest expression of the natural and authentic man (contra Locke’s claim that Christianity gives us the natural law). At the same time that Strauss rejected the metaphysics of the West, he could use his natural rights idea to acknowledge the clear truth that the liberal West was better off than, for example, Soviet Russia.

So what is Strauss’s aim in undermining Locke and applying Wite-Out to Locke’s theological assumptions? Up to now I have given a very straight reading of Strauss. Strauss is an enigmatic character, and my understanding is less than complete, but I will give my tentative conclusions on the motivations behind his (mis)treatment of Locke. You might call them my hypotheses. If you are cynical you might say I am giving a Straussian reading of Strauss, but that is not my intent - my aim is to stay true to the text. I would love any feedback on these:

- Strauss’s grand project was the replacement of Western Christian metaphysics with a godless moral-relativist natural law philosophy.

- Locke and classical liberalism are a roadblock to Strauss’s project if the common perception is that Locke’s liberalism 1) gave rise to the prosperity and egalitarian ideals of the West, and 2) arose directly from Christianity as claimed by Locke himself. In other words, Strauss sought to make us forget that Christianity can be thanked for the success of the West, by attacking point 2.

- Strauss described Locke as “the most famous and the most influential of all modern natural right teachers.” In order to advance Strauss’s godless natural law he would need to contend with Locke’s theologically-oriented natural law. In other words, Strauss sought to convince us that God is not necessary for morality.

- Therefore, it is in the interest of Strauss’s grand project to attempt (successfully, as it happens) to sever the logical connection between John Locke’s classical liberalism conclusions and his Christian assumptions.

The blame for the secularism of our age does not fall on Locke, as is often claimed by “post-liberal” conservatives today who take for granted a Straussian reading of Locke. On the contrary, there is a case to be made that by obscuring the Christian origins of Western liberalism, and by proposing a godless morality, the Straussian reading of Locke itself has contributed to the acceleration of Christianity’s decline since the mid-20th century.

I read your comments on Voegeln View and the West Coast Straussians do NOT support that view you attribute to all Straussians, that Locke is just posing as a Christian.

ReplyDeleteThanks for coming over here to leave a comment, Trent. I’m now interested in learning more about the West Coast Straussians. Out of curiosity, would a West Coast Straussian contend that Strauss himself didn’t teach that Locke was posing as a Christian, or do West Coast Straussians consciously break from Strauss in this?

ReplyDeleteThey break and a great exponent of that is Thomas G West and Larry Arnn, both Hillsdale people. Here is a video and an article that will start you off, the article is the place to begin

Deletehttps://hughhewitt.com/dr-larry-arnn-dr-thomas-west-john-locke/

Transcript , search for "so the low critique of Locke by conservatives is wrong..."

And here is West's short article detailing the true Locke

https://www.hillsdale.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2013-Lockes_Neglected_Teaching_on_Morality.pdf

Thanks for the links! I love the article. West is spot on in his assessment of Locke. My only concern is that he lets Strauss off too easily.

DeleteAgreed !! Strauss electrified his audience of present-day Straussians but when a master makes a mistake it is like Aristotle's "a heavier ball falls faster" and lasts for a long time in a multitude of places. I taught at a local Catholic seminary for 5 years and they use Strauss for their Political Philosophy course but don't know the recent work on Locke (who was not the force behind the Glorious Revolution, who did support toleration of Catholics, etc) and people like Jaffa are unknown

Deleteand here is the conversation on SoundCloud of Hugh Hewitt interviewing Larry Arnn and Thomas G West on John Locke ...and the wrong wrong view that Strauss initiated. Both Arnn and West are Straussians but West Coast Straussians of the Claremont school. Harry Jaffa epitomizes the -- to me -- correct view of John Locke

ReplyDeletehttps://soundcloud.com/hillsdale-college/hillsdale-dialogues-10-17-14-locke